Welcome to Art Life Balance, a twice-monthly newsletter about media, culture, and the creative process. If you enjoy this newsletter and would like others to find it, please like, share, and subscribe!

In attempting to understand his son’s resistance to repairing his own motorcycle, “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” author Robert Pirsig draws a line between two ways of thinking: the “romantic” and the “classical.” Romantic thinkers, he muses, are interested in what something is, as defined by its immediate appearance. Classical thinkers, on the other hand, want to know what it means, what it can do.

Pirsig describes his son as a romantic, interested in motorcycle-riding mostly for the feeling of the sun on his face and the wind in his hair. Thinking about the literal nuts and bolts of motorcycle repair harshes his desire to get away from it all. Meanwhile, for Pirsig, “it all” is a major part of the appeal. A classical thinker, he’s fascinated by the way each part of the motorcycle contributes to the functioning of the whole, and he enjoys fine-tuning them to optimize the machine’s potential.

Classical and romantic thinkers have trouble seeing eye to eye, Pirsig argues, because they each view the world through a totally different lens:

I’m only about 100 pages into the book, so I’m not sure how our author’s thoughts on his own dichotomy will shake out, but the comparison got me thinking about my own predisposition: Namely, how the “romantic” label explains why I’m compelled and repelled by certain approaches and ideas.

Like Pirsig’s son, I emphasize the visual, and I avoid solutions that are ugly or uninspiring — even if they’re functional. I chose my college largely for the look of the buildings. I prefer Macs to PCs. I’ll leave system updates on ice for weeks on end, and if you ever catch me reading an instruction manual, you can be sure I’ll be wearing a pissed-off expression. What’s more, I see the technological devices I own as as a means to an end. My iPad is an instrument for writing or making digital art: I know I have to tune it sometimes, but I only do so insofar as it’s necessary to start playing.

In sum, I don’t want to categorize and calibrate. I want to intuit and ideate — or as Pirsig would say, “groove.”

For the most part, I’m glad to be this way. I believe our culture suffers from a lack of romantic thinking. We construct cookie-cutter gray boxes instead of inspired architecture and wonder why people are hostile to new building projects. We valorize categorization and specialization and demean divergent, experimental thinking. We embrace statistics and hand-wave personal anecdotes, remaining willfully blind to the wisdom of stories. We seek the most efficient route to completing a task instead of the one that brings the most joy, intrigue, or fulfillment. We forget that style is substance, and it often implies function. Or that the values communicated by the look and feel of our products influence our own.

But sometimes emphasizing appearances can get you in trouble.

I smashed into this lesson a few days ago as I smashed into the cold hard ground at a science museum, where I foolishly accepted a coworker’s challenge to race to a wall and back. I never made it back. Instead, in a scene reminiscent of “Paul Blart Mall Cop 2,” my knee buckled on the turn and I fell to the ground in pain, only to be wheel-chaired away before an audience of mostly small children. It was decidedly not groovy.

Worse, it was predictable.

I’ve lived with a partially torn ACL and meniscus in my right knee since twisting it at a soccer game more than three years ago, and I’ve since re-injured it multiple times. Each time, after about a week of hobbling around the house post-injury, the knee seemed fine, so I decided not to get the surgery that would provide a more permanent repair.

There’s an anecdote in “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” when Pirsig notices his son’s motorcycle showing signs of disrepair. Instead of saying something, he sits on his hands, fantasizing about his son finally realizing why It’s Very Important to Maintain Your Motorcycle. Of course, things don’t work out exactly that way: His son is more resistant to repairing the motorcycle than Pirsig anticipates, and when he does decide to repair it, he rejects the solution his dad offers.

As someone who has been on both the giving and receiving end of unsolicited advice, this story made me laugh. For better and worse, humans are stubborn creatures, and our dispositions run deep. People aren’t receptive to wisdom they never asked for, and — maybe especially among romantic types — it takes personal experience to disrupt familiar modes of thinking.

As for me, the third fall in the ACL saga is the last straw. I’ve decided to get the surgery this time and to do the research necessary to get it done right. The most difficult part will be sticking to this conviction in a few weeks when I feel fine. For that, I’ll have to put on my “classical thinking” cap, remembering that appearances can be deceiving.

Fortunately, it’s a cap that fits more comfortably than it used to.

Although it’s not my default way of engaging with the world, I’ve begun to appreciate learning how things work, even if I tend to do it only when life forces my hand. Take technology, for instance. I have little inherent interest in algorithms or terms of service or datasets or business models or corporate structures: But an increasingly unpleasant feeling about many of the products and services I use provoked me to learn more about how they work and the incentive structures that inform their design, and that intellectual journey has been illuminating (if also disturbing).

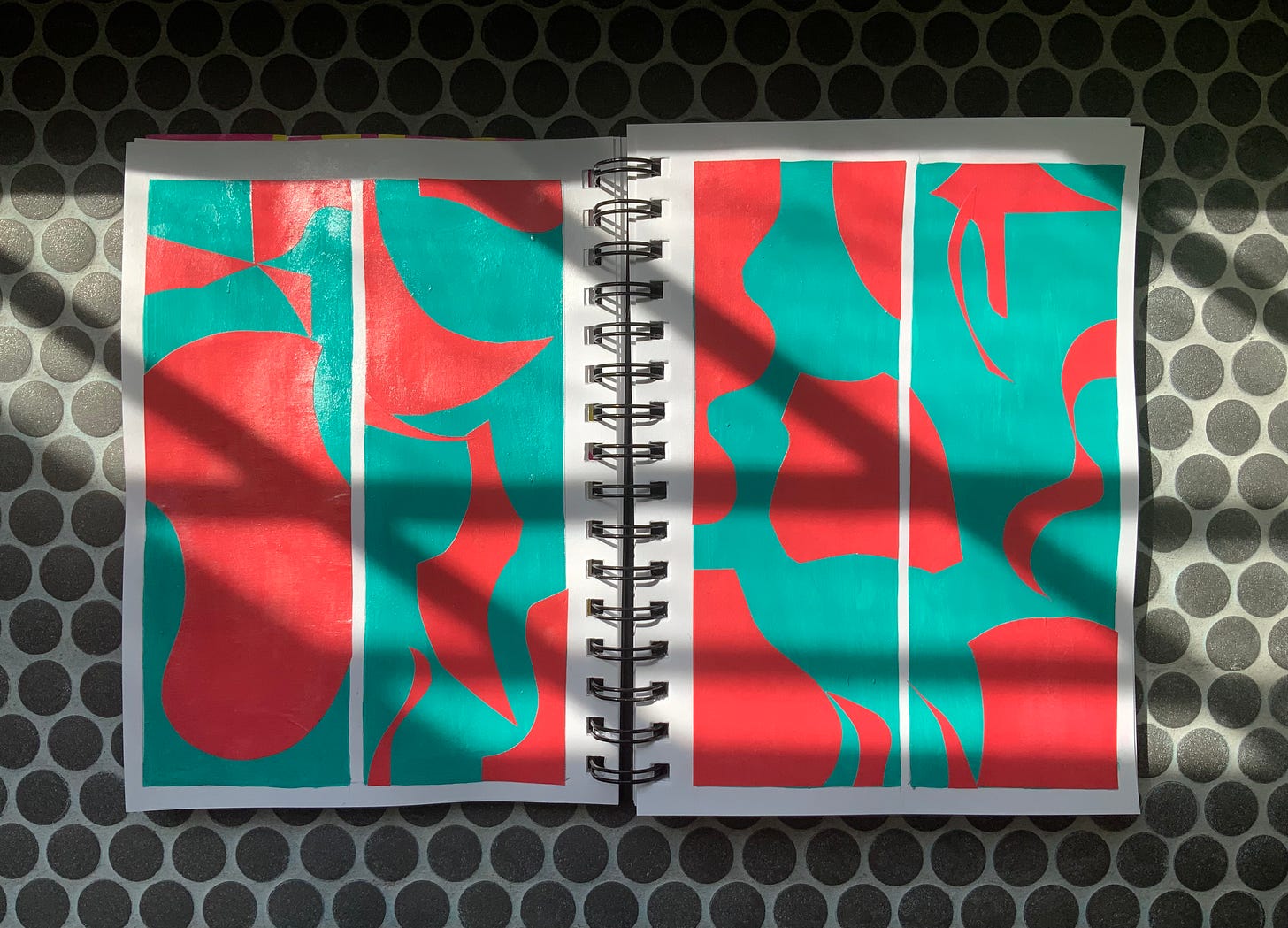

In a more positive example, I became interested in film photography because of the visual and tactile qualities of photos shot on film. Achieving the desired effect required building up a basic understanding of how each element of the camera and development kit functions. The best part of this effort has been realizing that the more often I put my newfound knowledge into practice, the more second-nature it becomes, until eventually, grinding becomes grooving.

These experiences go to show that it can be useful to think about romantic and classical thinking not as irreconcilable opposites, but as compatible tools. Romantic thinkers might begin with intuition, but switch to analysis when they hit a snag, if only to return to feeling things out. Classical thinkers might prioritize analysis, but in experiencing the fruits of their labor (the sun on your face, the wind in your hair) find inspiration for further study.

We err not by seeing the world primarily through one of these lenses, but by failing to acknowledge the value in the other.

Further reading: Don’t Doomscroll. Garden

My love-letter to gardening was published in ! The piece explores (and possibly reconciles?) two interrelated reasons for picking up this hobby: Fantasies of control and hopes of letting go. I’m unusually happy with how it turned out, and I hope you’ll give it a read!

Thank you for reading Art Life Balance.

If you have thoughts about this post, I’d love to know. Sound off in the comments!

If you enjoy this newsletter and would like to support it, consider becoming a paying subscriber. At this tier, you can opt into Print Club and receive quarterly art gifts in the mail. You’ll also receive Mood Board, a quarterly collage-style newsletter.

Very interesting analysis, thanks for writing about it. I like the understanding you have of your own place on the spectrum of romantic thinking and classical. The connection of this with how you’ve dealt with your injury is illuminating.

I think I fall on the “romantic-classical” spectrum at about 70%-30%, respectively. I lean into learning more deeply about things that are affecting me more immediately. I know just enough about how my phone works to be able to operate it and troubleshoot surface level issues. I’m probably not going to take a course in superconductors, though. This may not be the best example, but I think you get it.

As soon as I started reading this post, I thought, "But we need _both_ those types of thinking!". So I was pleased to find out that was your point. Lovely film photograph by the way!